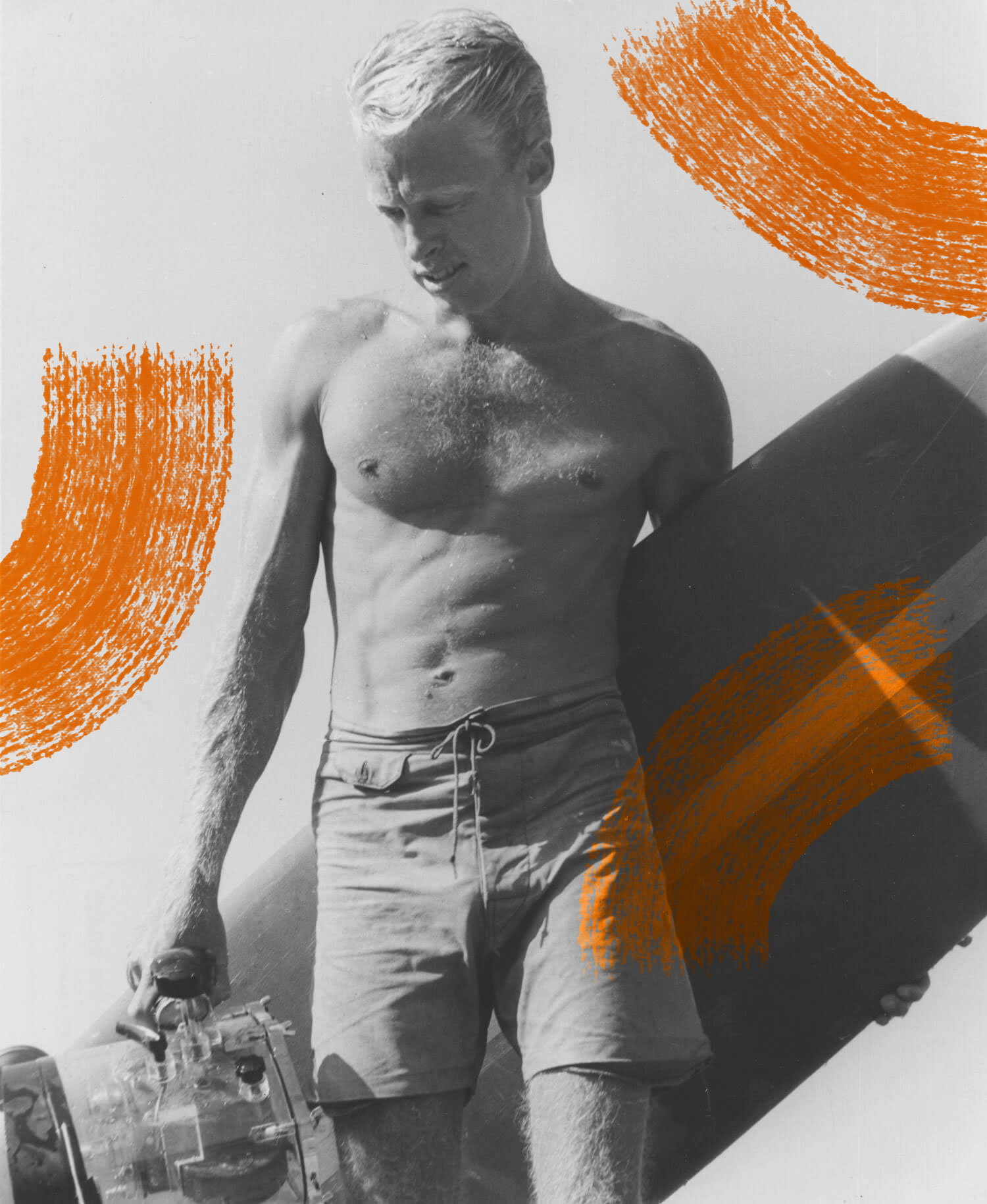

Bruce Brown

Born in San Francisco, Bruce grew up in Southern California. He started surfing at 11 on the green rollers that formed at the entrance channel to Alamitos Bay before the Long Beach break wall was completed. He attended Wilson High School (class of 1955), where he was a gymnast, but really, he says, “I majored in not going to school.”

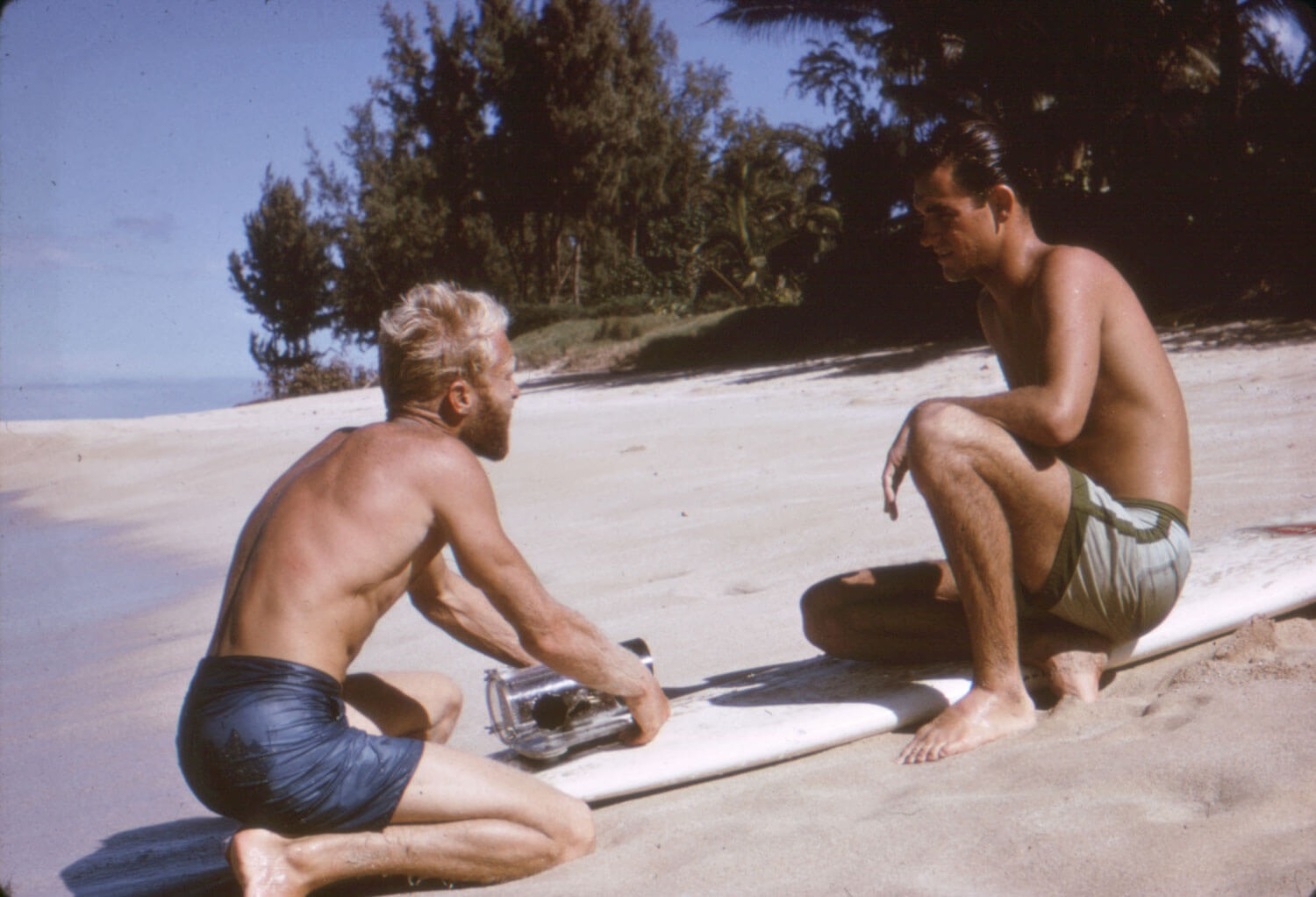

Instead, he spent more time at the beach. He first used a still camera to show his mother what surfing looked like. A regular at the Huntington Pier-Seal Beach area in high school, he enlisted in the Navy after graduation, went to submarine school, and finished at the top of his class to ensure his pick of assignment, which was Hawaii. Besides surfing Ala Moana in those mid-50s glory days with California transplant Jose Angel and others, he started shooting his first 8mm movies.

Early films

After his discharge in 1957, Bruce returned to California and worked in San Clemente as a lifeguard when a flush Dale Velzy (“World’s Largest Manufacturer”) put up $5,000 for a film that would promote the Velzy surf team. “That covered the cost of the camera, travel and a year’s living expenses,” Bruce later explained.

It was a journey that would become familiar — surfing California, traveling to Hawaii, driving in goofy beaters and sleeping on beaches. The resulting film, narrated live by Brown along with an offbeat Bud Shank soundtrack, was Slippery When Wet. Bruce took the thing on the four-wall tour in 1958, following in the footprints of pioneer Bud Browne and paralleling another rising cinematographer, John Severson.

Surf Crazy, Barefoot Adventure, Surfing Hollow Days and Waterlogged followed, and Bruce’s success followed the same curve as that of surfing in those early boom years. His lens documented the meteoric rise of a cult sport. In the winter of 1961, while in Hawaii with Phil Edwards making Surfing Hollow Days, he filmed Edwards’ groundbreaking first rides at the Banzai Pipeline.

On Any Sunday

After The Endless Summer, Bruce built new offices in Dana Point, California, and went to work on a film about his other passion — dirt bikes. The resulting documentary, co-produced by his friend, the actor Steve McQueen, earned On Any Sunday (1971) an Academy Award nomination

After work

Never much drawn to cities or even crowded theaters, Bruce moved his family (wife Pat and kids Dana, Wade and Nancy) to a remote ranch north of Santa Barbara around 1980. There Brown surfed, rode his motorcycles, built a house, got into car restoration, raced sprint cars around his track and, more recently, got into rally cars — an all-wheel-drive turbo-charged Mazda that he and Pat co-race. “We try to stay upright as much as possible,” he says.

Bruce came out of retirement in 1992 to go on safari making the Hollywood-sequel Endless Summer II (released in 1994 by New Line Cinema), a reprise of the original with Robert “Wingnut” Weaver and Pat O’Connell leading the search But Brown was disappointed with the process and the result. “I never made any money, except what they paid me to direct it,” he says, adding that they basically ignored him once the film was done. “They got bought out by Ted Turner and kind of lost interest in our little product. It was kind of unpleasant, more like a battle than cooperation.”

The Endless Summer

The formula was effective, but the market was getting crowded with more and more surf films. In 1963, Bruce decided his next film needed a different twist — two surfers, Robert August and Mike Hynson, would take advantage of the fact that when it was winter in the Northern Hemisphere, it was summer in the Southern. The concept was simple and profound — you could live in a surfer’s paradise, an endless summer.

Released in 1964, The Endless Summer was Bruce’s most successful surf film, playing to sold-out theaters in the United States and Hawaii. Audiences were so encouraging that Brown became convinced that this was a movie that even non-surfers could enjoy.

The tale of Bruce’s campaign to take The Endless Summer to the American heartland is testament to the filmmaker’s creativity and persistence. In 1966, the film opened in theaters across the country, and Bruce Brown became surfing’s greatest success story.